Meat preservation has been part of human experience for millennia, and something most cultures have in common since mankind learned early on that food preservation techniques were as critical for survival as hunting. Since meat begins the process of spoiling soon after it is harvested, knowing how to preserve food and make supplies last longer by freezing and drying also enabled ancient hunter gatherers to live in one place and form communities. Sugar has long played a key role in meat curing by aiding in preservation and enhancing the flavor of the long-lasting finished product.

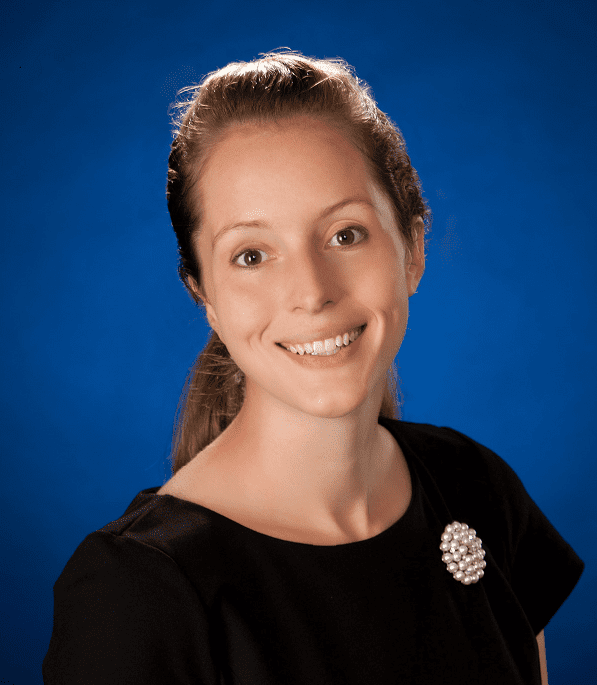

In the modern era, meats such as ham, bacon and jerky are typically preserved using a brine containing sugar, salt, and other ingredients, according to Julie Garden-Robinson, Ph.D., R.D., L.R.D., professor and food and nutrition specialist at North Dakota State University (NDSU).

“After the brining process, heating and/or smoking follow, and sugar plays a role in preservation because it has hygroscopic properties,” Garden-Robinson said. “This means that it ‘holds on’ to the moisture, reducing the water activity of the preserved food.” Water activity in food refers to the amount of unbound or free water available for microbial growth and chemical reactions.

“Water activity is a scale from 0 to 1.0, with 1.0 being pure water. Most types of bacteria need a water activity of 0.85 or greater to grow, so that number is typically used as a benchmark in food safety,” said Garden-Robinson. “Sugar’s hygroscopic properties makes water less available to both spoilage organisms and organisms that cause foodborne illnesses. This aids food preservation by slowing the growth of various microorganisms. Dried foods have a lower water activity and are typically safer and more shelf stable.”

In addition, Garden-Robinson said most preserved meats also include nitrites and nitrates as a chemical curing agent. The addition of nitrite is the main determinant of the pinkish color of cured meat and also helps prevent the growth of Clostridium botulinum, which can produce the extremely dangerous botulinum toxin. However, not all bacteria are harmful. There are beneficial bacteria that are an important part of the preservation process for some types of cured meats, such as fermented sausages.

“Fermented sausages, such as summer sausage, usually rely on the growth of Lactobacillus bacteria, which uses sugar in fermenting and producing characteristic flavors. Lactobacillus bacteria use sugar as ‘food’ to produce various types of acid that lower the pH of the sausage,” Garden-Robinson said. “During this process, specific flavors characteristic of a fermented sausage are produced. A reduction in pH provides the tanginess or slightly sour taste and also can enhance the shelf life. Some types of fermented sausage do not require refrigeration as a result of the low pH that develops from the fermentation process.”

Sugar also adds a characteristic sweet flavor to cured meats by teaming up with salt to create the flavors we know and love.

“Sweet and salty are distinct tastes detectable by our tastebuds. Sugar and salt act together in creating flavor profiles and enhancing our enjoyment of foods,” said Garden-Robinson. “In fact, salt and sugar are paired in culinary uses, such as salted caramel, and sugar acts to help balance the salty sensations. Salt, on the other hand, brings out the natural sweetness of some foods. For example, some people like to salt their slice of watermelon in the summer, because the salt draws out the naturally sweet juices.”

Few things are more enjoyable than a delicious slice of crispy bacon or perfectly browned sausage. Sugar plays a direct role in achieving these textures, according to Garden-Robinson.

“Typically, sugar contributes to color development through the process of caramelization in foods like candy,” she said. “During cooking of cured meat, such as bacon or sausage, sugar can promote browning on the exterior.”

Hunting wild game is a beloved tradition and way of life in many parts of the country. Safety is of paramount importance not only during the hunt, but also when preserving the results of a successful expedition.

“There are many food safety tips for safely preserving meat in NDSU Extension’s publication, ‘Jerky Making: Producing a Traditional Food with Modern Processes,’ and these principles also apply to other types of preserved meat production,” said Garden-Robinson. “There are tips for safely sanitizing kitchen surfaces, thawing and storing meat, and using a food dehydrator.”

Garden-Robinson urges everyone interested in meat preservation to seek out up-to-date information about food preservation and be wary of information found in old cookbooks.

“Also available from NDSU Extension is a publication called “Wild Side of the Menu” which provides guidelines for the safe preparation, processing and preservation of wild game. Raw meat is, of course, very high in protein and moisture, which promote spoilage and potential food safety issues unless kept cold and/or cooked properly. It can also be contaminated with pathogenic bacteria that can lead to serious illness or even death,” she said. “Cases of foodborne illness have been linked to unsafe home preparation of jerky, which prompted changes in consumer recommendations. We now promote heating the strips of jerky meat prior to drying it.

Garden-Robinson recommends everyone be aware of resources provided by Cooperative Extension at land grant universities throughout the US when processing meat.

“Knowledge and experience of the hunter and weather conditions during the hunt can influence the safety of the final preserved meat. Wild game might not be handled in as safe a manner as commercially processed meats, which is subject to inspection, food safety regulations and a controlled environment,” she said. “However, regardless of the source of processed meat, we need to take some special precautions to ensure its safety, whether we prepare it ourselves or buy it. Online resources and both online and face-to-face training are widely available through Cooperative Extension.”

Get Social with #MoreToSugar